Scripture: Matthew 11:25–30

“Open my eyes, that I may see glimpses of truth Thou hast for me.”

These were the words that we sang a few moments ago, and the lyrics of one of my favorite hymns. They beautifully introduce us to this summer’s worship series. If you read in the newsletter, you already know that our series for the next several weeks is titled “Art and the Gospel.” The goal is to explore various forms of art that are not considered “Christian,” or even “religious,” and yet seem to reveal profound truths about who God is in our world. They reveal “glimpses of truth” such as the song suggests. Last week, Nathan used an Anne Sexton poem in his sermon on Paul. Next week, Pastor Cristina is going to preach about the Disney musical Encanto. The point of the series is to suggest that we are surrounded by images and stories and music that may not intentionally be about Jesus or Scriptural themes, and yet, in this art, we find God. We see themes of grace and sacrifice and love and creative beauty. It is the idea behind Sanctuary of the Cinema, led by our own Chad Johnston, searching for profound truth and deep spiritual themes in all sorts of movies. It is the truth behind Clara Scott’s words: “open my eyes, illumine me, Spirit divine.”

So the goal each week will be to have one eye on the Scriptural story, another eye on a cultural/artistic parallel, and a third eye (?) on our own context and walk of faith.

For example, today’s passage comes from the Gospel of Matthew. To set the context, it is good to remember that Matthew is writing these words to Christians, perhaps to a congregation or a cluster of congregations, at least a generation after Paul wrote letters to the Philippians and the Romans. Some of the initial excitement of the Early Church has waned, and it seems that there was probably a general sense of anxiety amongst those in Matthew’s church. There was suspicion from those outside of the church, and infighting and disagreement within the church. The Gospel writer wanted to speak to that anxiety,

Which feels connected to our world today, doesn’t it? Rumors of a recession, following the economic disaster of the pandemic. Inflation and soaring prices, as manufacturers and suppliers are not keeping up with the demand. High gas prices squeezing us all, but especially the most vulnerable in our midst. And this week, many of us watched images and heard testimony and evidence of a violent and deluded attempt to overthrow our democracy on January 6th of last year. Anxiety abounds.

And let me add a third layer to this. A third age of anxiety. Henry Ossawa Tanner was born in 1859. His mother escaped slavery in the South by way of the Underground Railroad. In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, she met and married his father, an AME bishop, activist, and eventual friend of Frederick Douglass. Henry’s middle name, Ossawa, was a tribute to those who died in Osawatomie, Kansas, when violent and destructive pro-slavery forces crossed the border into Free State Kansas, seven years before Quantrill’s Raid. Henry turned 6 two days after June 19, 1865, the day that the last slaves were freed on US soil, the day that we now celebrate as Juneteenth, or Emancipation Day. When Henry was still young, the family moved from Pittsburgh, where he was born, to Philadelphia. And it was there that young Henry fell in love with painting. Even as a child, he would paint pictures that would catch the eye of other artists in town. Before long, he had enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, even though it was rare for a painter to accept an apprentice who was Black. Tanner became known as one of the first and most famous Black painters after the Civil War, indeed in American history. But, as you can imagine, it was not an easy time for African-Americans such as Henry and his family…a context that we see reflected in one of his greatest works.

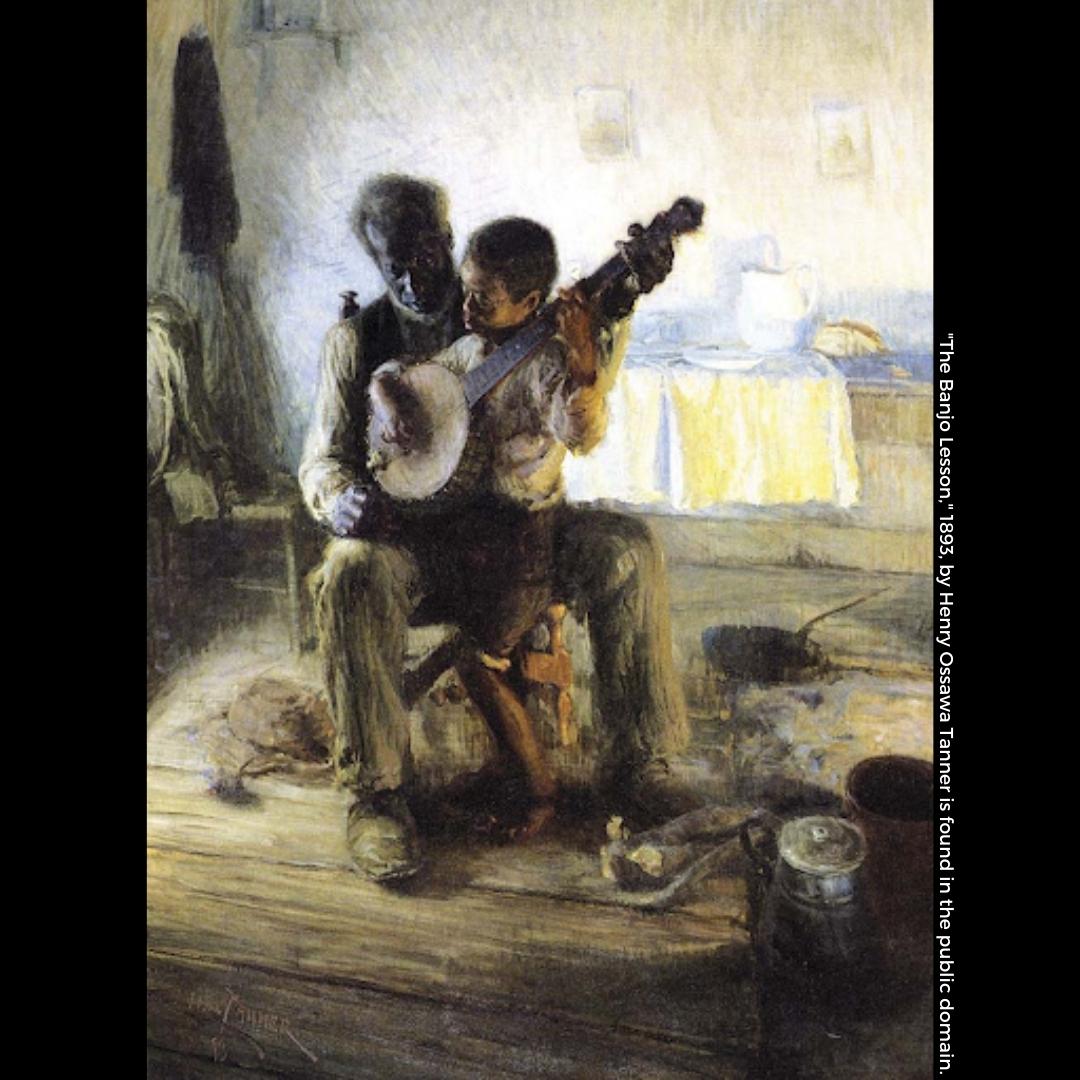

One of Henry Ossawa Tanner’s most famous paintings is titled The Banjo Lesson. It is a simple yet beautiful depiction of a young boy learning to play the banjo. An older man, perhaps his grandfather, or an uncle or family friend, or even his father, holds the banjo with him. Both of their hands are on the strings, and the boy is half-standing, half-sitting in the older man’s lap as he learns about how to play the instrument. The context of the piece would have been a difficult and challenging time in the early years after slavery was abolished. This Black man and Black boy would have faced skepticism from the culture around them, and struggled to make ends meet within their community. The room in which they learn is not opulent, nor are their clothes expensive. Even the instrument that they play is symbolic of the limitations placed on them. The banjo was traditionally an African instrument, and it was more socially acceptable for African Americans to play it than many other instruments from European heritage, such as the violin or organ. Like the Gospel of Matthew, just beyond the edges lay a context of anxiety and limitations.

And yet, there is a profound sense of care in the midst of such anxiety. Like with so many of Tanner’s paintings, the scene comes alive. You can almost hear the twang of the wrong notes as the boy tries to figure out the difficult instrument. And you can imagine the older man’s patience as he helps the boy with where to place his fingers and how to strum the strings. The scene is intimate; the boy is barefoot as he learns in what looks to be a simple home, with a table behind them and a cook stove and fire in the foreground. Here, in the warmth of the fire, the patient teacher shares his knowledge out of a deep and loving relationship.

Which, of course, is a beautiful parallel to the passage I read earlier from Matthew. Into the anxiety of Matthew’s world come the words of Jesus: “For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.” A salve for weary souls. Scholars suggest that the Gospel of Matthew was a sort of teaching tool, in order to help guide these anxious and concerned Christians by way of the stories and words of Jesus. The Sermon on the Mount, the Temple Teachings of Jesus, and the Gospel as a whole was meant to be a lesson in “the Jesus way.” Live this way, and the struggles and difficulties you face can be met.

The passage begins with Jesus’s words about his relationship with the One that he calls Father. Did you notice the language of intimacy? Of relationship? Of connection? This passage is often used to help us talk about the theology of the Trinity, because it helps us to understand that the foundational nature of reality is relational. God is eternally in relationship. The image I picture is much like Tanner’s loving parent figure, holding a young boy in his lap. It is an image of relationship, of love, of trust. It’s the language of gratitude that Jesus uses for the One he calls Father.

And then, in the passage, the language shifts. Jesus the teacher has shared some hard words in the Sermon on the Mount, but it is not as the harsh taskmaster, but a loving grandparent teaching his beloved grandson. Now, Jesus becomes like the old man in the painting. A caring nurturer, gently holding the little one in his lap. Gently, Jesus teaches us with a wisdom that is unexpected and relational. This is what we mean when we talk about having a relationship with Jesus. Instead of a heavy yoke—a heavy burden—of obligations and requirements and expectations, the way of Jesus is first and foremost easy…light…loving. About connecting with, forming relationship to, and building trust with both God and each other. Matthew’s Gospel here tells us that it’s not about simply knowing things. It is not about simply doing things. It is about being in relationship. Cultivating that relationship, in a way analogous to the relationship between Jesus and the One he called Father. It is not accidental that Jesus uses language of infants. Children who are deeply reliant on the care and love of adults, often including parents. Jesus’s invitation is to humility, not resting on our own work or wisdom, but in the loving reliance of a trusting child.

“Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.”

A salve for Matthew’s church, and for our anxious world. I think about the multiple layers of what is happening in this painting. At face value, the older man is teaching the boy, through intimacy and loving relationship. But I also think of the way that Henry Ossawa Tanner both learned and taught the same way. Other Black painters in Philadelphia showed him that this was something that he could do. In turn, he became a mentor to others, serving both in the United States and in Europe as a role model for Black artists who followed him.

I wonder who those people have been in your life? Who are the people who have taught you, lovingly, caringly? Who are the ones who pulled you up on their lap and gently taught you? Fathers, mothers, grandparents, aunts and uncles, family friends? I am thankful for my own father and mother, who taught me about love and grace and how to care for people different than me, how to listen to them and receive them with grace. I am thankful for my grandfather, who taught me practical lessons about physical things like tools and cars and fishing tackle. I am thankful for my grandmother, who taught me how to serve, showing me what a servant looks like by way the cool sheets of a bed already made and ready after a long trip, by a plate of hot waffles when I woke up, or by a lifetime of service in the school system. Each of them taught me with the same tender care as the man in the painting, pulling me onto their lap and comforting and correcting.

And on this Juneteenth, I find myself thankful for other teachers. People of color who gently but clearly helped me to see dangers of racism through their eyes. Helped enlighten me and emancipate me. Juneteenth is not just about liberation of Black people in this country, but it really is more about liberation of white people. It is about emancipation from assumptions of power and privilege and supremacy. These are the things that these wise teachers have taught me, helped me to see, glimpses of truth that God spoke to me through them.…

- I am thankful for Dr. Scott Williamson, who alongside the Niebuhr brothers taught me about the dangers of authoritarianism in any age.

- I am thankful for Rev. Dr. Dale Andrews, who taught me about the human experience, especially the experience of being Black in America.

- I am thankful for Rev. Dr. Stephanie Crowder, who challenged me as a preacher to be mindful of ways that I insert my own assumptions into the text and my sermons.

- I am thankful for Rev. Dr. Joy J. Moore, who taught me that the stories of our culture are connected to the stories of our Scriptures.

- And I am thankful for Rev. Dr. Frank Thomas, who taught me that in the end, a sermon must be a celebration of the grace and joy and hope that only God can give.

These African American teachers and mentors and guides patiently walked me through some bad notes and out of tune chords, guiding my fingers to learn the right way. They helped me see Jesus with new eyes, and pointed me to the one who both comforts and confronts. Carries and corrects.

Henry Ossawa Tanner had an incredible mastery of light and he found a way to take normal, ordinary, everyday moments and paint them with incredible beauty. He also painted many Biblical images, but found a way to make them seem intimate and real, as if they were events unfolding in our time. His depiction of the Annunciation to Mary is amazing, especially the way the light plays on the room and on Mary’s face.

Look again at The Banjo Lesson and see the way that he paints with light. There are two types and two sources of light in the painting. In the background, we can see sunlight streaming into the room. Bright, filling, complete. But there is also the light from the fire that is reflected from some place in front of the image. Softer, but still warm and inviting.

Perhaps this is the final word that we might consider, for this sermon and for the series as a whole. We know that the brightest light in our lives is the experience of God, showing love beyond our comprehension. We cannot even look at its brightness lest we burn our eyes. Yet there is another type of light. Softer echoes of God’s holiness and brilliance. These are the lights who surround us, who teach us, who pull us onto their laps and comfort and correct. Who teach and show love. Let us thank God today for our teachers. Our fathers and mothers. Our grandparents and aunts and uncles and family friends. Our academic and instructional mentors. All willing to suffer through plenty of bad notes in order to help us make music with our lives. Willing to pull us onto their laps, and show us the way.

Leave a Reply